Viriah reviewed by Jairam Reddy

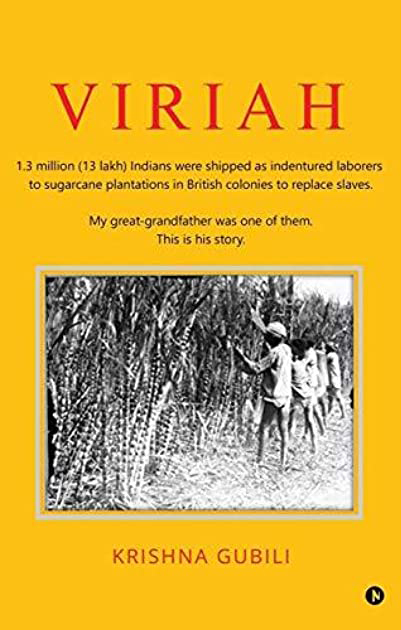

Viriah by Krishna Gubili, a fascinating and personal account of intensive archival research, constructing the family tree and providing an intimate account of indenture in the sugar cane fields of the then Natal province in South Africa was published in 2018. In the context of the 159 years of the arrival of Indian indentured labourers, this book provides a rich, intimate and textured history of indenture.

Krisna Gubili, an Indian citizen, from Hyderabad, was told by his grandmother, about his great-grandfather who had emigrated to South Africa through the system of indenture. As a teenager he often wondered about what had happened to him in SA and what sort of life he had led. His grandmother told him that Viriah, his great grandfather worked in the sugar cane fields and at one stage he was promoted to being a “Boiler Sirdar”; she also told him that he had met Gandhi while he was in SA and he wept when Gandhi was assassinated in 1947?

During the routine task of house cleaning, Krishna found a letter with a South African stamp in the chest lying in the attic of the house. This letter was written by the son of the daughter of his great grandfather, Daniel Naidoo. Krishna replied immediately but did not receive a reply from South Africa. Krishna’s interest in South Africa was rekindled when he watched Nelson Mandela being released on February 11, 1990 after 27 year of imprisonment. In March 1995, a letter had arrived from South Africa. It was from Daniel Naidoo, grandson of his grand-fathers sister and hence his cousin, 2 years older than him. Daniel had two children – Danae, 8 months old and son Casere, 4 years old. Krishna replied immediately but again did not receive a reply from Daniel.

Krishna, an engineering graduate with MBA relocated to Minnesota, USA with his wife in June 1998. He read Mandelas Long Walk to Freedom and came to know the role played by Indian stalwarts like Yusuf Dadoo, Ahmed Kathrada in the struggle for the country’s liberation. In 2000, much to his delight and surprise he found a facebook picture of Danae Naidoo. He followed up with a message and received a reply. He soon was in telephonic conversation with the family in Tongaat, KZN. He spoke often and emailed Daniel but did not elicit much information of his great grandfather. His grandmother turned 90 in 2013 and passed away in 1914 while in June of the same year Daniel passed on in SA.

Krishna decided to travel to South Africa. He boarded a flight at JF Kennedy Airport, New York on 21 December 2014 and arrived at King Shaka airport via Johannesburg on 22 December. Cesare, the son of Daniel Naidoo and brother of Danae was there to meet him. He drove him to the family home in Tongaat where he met Daniel’s wife and Danae; Daniels brothers Filly and Trevor were there too. The traffic in Durban chaotic as in India made him feel very much at home. He was blown away by the affluence of the suburb of Umhlanga and enjoyed the hospitality of dal, chicken and rice at the Naidoo home.

The next day he visited the Durban archives but could find no further details of his great grandfather. He arrived at the Pietermaritzburg Archives at 10am on Christmas eve. After painstaking perusal of the ships lists, at 12.15 pm Krishna was overjoyed to find his great grandfathers details on the ships register of 1932. Viriah’s details on the ships register were as follows;

- Indenture No: 106051

- Name: Guvvili Viriah

- Fathers Name: G Ramanna

- Born: 1882

- Age (on arrival): 22

- Village: Koorlapad

- Date of arrival: Aug 28th 1904

- Ship: Umkuzi XVI Madras

- Employer: Addison, Friend Herwill & Gledhow Stanger Sugar

- Date of return: Nov 16th 1932

- Passed away: 1952

Ramaiah Gubili and wife Papamma, working farmers had 4 children – daughters Lakshmi, Durga and Saraswathi and son Viriah. Eldest sister Lakshmi married Narayya, a failure and drug addict. Life on the farm was hard and his father could not pay taxes. Viriah, in his teens left school and began helping his father on the farm. There was no rain & farms were parched. The family jewellery was stolen and Viriah was blamed. In these desperate circumstances Viriah decided to leave home and head towards the village of Vijawada.

High caste government appointed emigration agents in Madras and Calcutta appointed sub-agents, the Arkatis, unlicensed labour recruiting agents who hung out in markets, temples, train stations, on the lookout for people needing work. They were recruiting labourers for the sugar cane fields in Natal with a promise of a salary 5 rupees a month together provision of house and food. This looked an inviting proposition to desperate labourers as a comfortable voyage across the seas was included. Arkatis also mentioned that money saved could be sent back to their families in India. For Viriah this and the other attractions convinced him to emigrate as an indentured labourer.

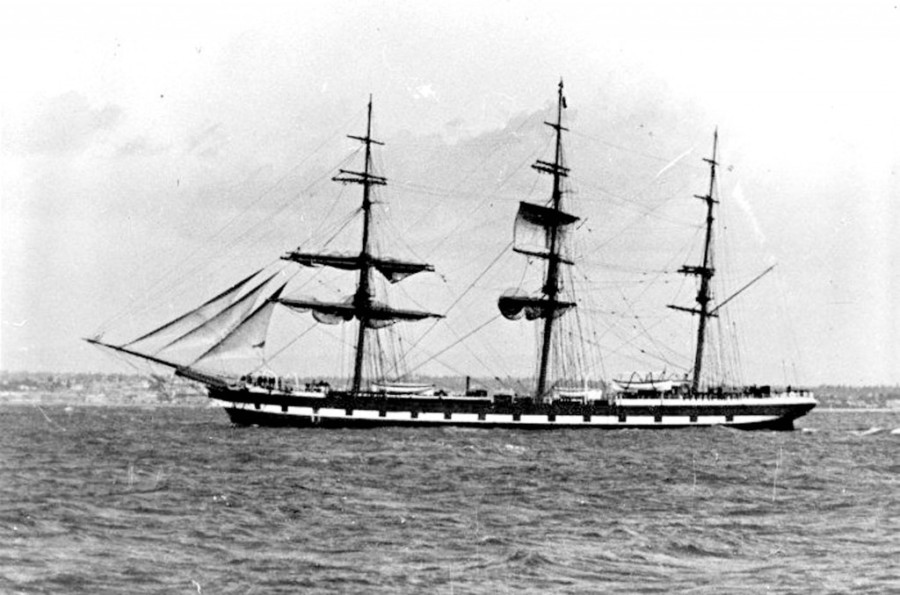

Viriah arrived with 100 recruits on a rattling steam train in Madras. On arrival, a doctor examined them and only accepted healthy ‘coolies’ for indenture. After the long train ride and medical examination, they waited, tired, hungry and thirsty; 400 coolies, some of whom have been waiting in this depot for over a month. Prior to boarding each recruit was given a blanket, 2 dhotis, two caps, a jacket, mug – in a bundle; each also wore a tin disc around the necks, their number. They departed on the ship UMKUZI with 614 ‘coolies’ of whom 154 were women. People in the ship came from all religions and castes – shepherds, washerman (dobis), potters, salt workers, brahmins, sayids (muslims), rajputs, pathans, land owning class, oil pressers. On the ship the caste hierarchy was beginning to breakdown as everyone was a coolie. All including women had to work on the ship – cleaning, cooking etc. One Rangamma complained off sexual assault by one of the ship’s crew. She was born to a potter’s family when her father passed, she was a married to a man old enough to be her grand-father. Her husband passed away. Widows faced horrendous conditions in the 19th century and she was easily recruited by an arkati. The long journey with cramped space, unhygienic conditions was the perfect condition for infections. After a 6 week journey the ship docked in the harbour on 28 August 1904.

On landing in Port Natal, they were moved to makeshift tents in a muddy terrain with no latrines. Following a medical examination on the following day, then were sent to the immigration register. The 614 Indentured labourers were distributed to sugar estates among 60 different companies. Sixteen labourers including Viriah and friends Shaikh and Venketsami were allotted to Gledhow Sugar Estate. They were duly escorted by a burly Zulu guard with a whip through a lengthy walk to the farms, 50kms away. Coolies young and old had to walk including pregnant women. It was dark by the time they got to Tongaat. They stayed in the shed of the Bristol Hotel. After breakfast they resumed their journey, reaching Stanger in the evening. They were welcomed to Gledhow Sugar Estate by Indian coolies who had been working in the GSE. They had a dimly lit room for their accommodation. Rice and vegetables were being cooked by a coolie woman; they enjoyed the hot rice and vegetable curry and went to sleep on the floor in their shed.

When Viriah and the others had arrived, the planting season was approaching. Land had to be cleared of debris and furrows dug for planting. They were met in the morning by their guard and Sirdar – master of the coolies was Hindi and most Tamils and Telegu speakers did not understand him. After an hour’s walk they reached the farm with the Sirdar on horseback. Weeding, clearing debris and digging furrows – by lunch they were tired and thirsty, drenched in sweat; One carpenter who asked about terms of the contract was whacked on the ear by the Sirdar. Four weeks later the farm was ready for planting; cane was carried in baskets and laid in furrows; each coolie had to plant 5 baskets of cane per day; if not complete they got an earful from the Sirdar or pay was withheld. After a fortnight young shoots of cane emerged; the cane matured in 10-14 months and grew up to 12ft in height. Rainfall was an all important factor in growth of cane. The coolies worked with naked feet and suffered insects bites, rock cuts and had to be aware of snakes and rats. Their bodies covered in mud by the time they left the farm after a day’s work. Sunday was rest day; they took a bath, went to the temple; in the evenings they sang, danced, drink and ate.

After 6 months Viriah wrote letter to his mother and handed it to Sirdar to send off but he was not sure if it was sent. They had to have a pass to leave farm. He was informed by parents Ramiah and Pappamah in India their daughter and his sister Lakshmi died. Harvesting was a busy season; cutting fields were burnt; workers tied cane into bundles and hoisted them on to the cart. Last day of month collies lined to get paid – with rations; there were no wage books; left to whim of Sirdar. Cane had to delivered to mill quickly & sirdars made them work furiously; both animals and coolies whipped by sirdars to keep them moving.

With the first 5 years of indenture coming to an end, Viriah then could become a free coolie. He was informed that after deducting house rent and transportation charges from India, he owed the farm 10 pounds. He should pay the amount or re-indenture; so he began his second period of 5 year indenture. “It rained incessantly all day and the coolies were at work with little protection from natures’ elements. Drenched to the bone, they returned to the barracks to find that the firewood was wet, which meant only cold mealies to satisfy their hunger”. While Viriah lay shivering in the shed, he remembers his mother making home-made remedies for him – boiling milk and sprinkling turmeric, black pepper, ginger, cloves, cumin. Sirdar deducted a month’s wages for 3 days sick leave

Women were paid half the men’s wages and rations for the same amount of work as men. For women it was a perilous journey. In addition to the crampness and unhygienic conditions, they had to ward of the advances of the arkatis, ship’s captain and doctors, sirdars and guards – an inhuman struggle they had to endure. The ratio of 4 males to 1 female on farms added to their woes. Because of scarcity of brides dowry was reversed – bridegrooms had to 5-10 pounds to the bride’s father. Men were bare chested and wore dhotis and turbans while women wore saris, made of cotton; with anklets, nose rings and bangles. A temple was built on the estate; they celebrated Diwali & Kavadi and sang bajans; 10% of immigrants were Muslims. Except for the few Africans who worked on the farms, rest were confined to reservations; both groups looked upon each other with suspicion.

A three pound tax was imposed on their earnings by a sirdar. One of the coolies mentioned that thanks to the efforts of a lawyer from India, Gandhi, the tax was reduced from 25 pounds to three pounds. They further heard that he had built an Ashram in Phoenix. One of the labourers, Bala, a recent immigrant had taken ill and was coughing incessantly. Despite the fact that he was struggling to wield the machette, he was whipped by the sirdar and Bala fell into the mud writhing in pain. Viriah managed to transport the fallen and ill Bala in an ox cart to Gandhi’s ashram In Phoenix for medical care. After listening to the distressing tale of Bala’s injuries Gandhi and his colleague cleansed his wounds and dressed them with bandages. Furthermore, he requested that Bala be kept at the Ashram for a few days before returning to the farm. Gandhi had written a letter of complaint to the Protector of Immigration Officer about Balas ill-treatment but nothing came of it. When Bala returned to Gledhow his ill-treatment continued. Eventually with assistance of Kishan Singh, a Sirdar at Huletts Estate whom Viriah had met at Gandhi’s ashram, Bala was transferred to his estate. Viriah had made several visits to the ashram to attend its prayer meetings. These meetings with Gandhi and visit to the ashram had left an indelible impression on Viriah.

With Viriah’s second indenture period drawing to a close, he became a free Indian. He bade farewell to Gledhow and headed for Darnall. He began work on Hulett’s farms which had higher standards, cleaner barracks and shaped the sugar industry in SA. By this time Viriah spoke Telegu, Tamil and Zulu. He married Rajamma and Sirdar Kishan Singh allotted land along the Umgeni River for Viriah. Viriah and Rajamma had 2 daughters and a son. Viriah was appointed new Sirdar of the farm. At this time the indenture system underwent major change. In the Bambatha Rebelllion in 1910, last struggle of Zulu against British, the colonial forces crushed the rebellion. Zulus now became a source of cheap labour. Thus the % of Indians on sugar farms fell from 88% in 1910 to 7% ibn 1945.

Although he received no reply to his letters from his parents, Viriah thought of returning home and helping his parents and return the stolen jewellery. Viriah departed for India in 1932 in the ship, Umzumbi after having spent 28 years in Natal. On arrival in India, he found that his parents Ramiah and Papamma and his sister Lakshmi had passed on but he was reunited with his sisters Durga and Saraswati. He acquired a sugar cane farm and returned to his former home village Vijawada. He lived to see India acquire its independence on 15 August 1947 but was devastated by the assassination of Gandhi on 30 January 1948. Viriah kept reflecting on whether he should have returned to India on the completion of his period of indenture. He passed on in 1952.

In his concluding chapter, Krishna Gubili explores the reasons as to why many Indians chose indenture between 1860 and 1911. The British had ruled India for 164 years from 1857 to 1947. During the period 1872- 1921, life expectancy fell by a staggering 20%; 21 million Indians died in seven famines between the years 1837 to 1900. The period of British rule from 1757 to 1947 saw no increase in India’s per capita income. India’s share of the world’s economy was 25%; after 300 years of occupation, India’s share fell to a mere 4%.

In the appendix to the book Krishna Gubili describes the Kafala System in the Middle East as a form of modern day slavery. It is estimated that 25 million migrant workers are employed in the countries of Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and Oman. These workers are largely from India, Pakistan, Bangladash, Phillipines, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. Many are illiterate, barely understand their contracts and are recruited by unscrupulous agents. Passports of migrants are taken for safe keeping and they need written permission to leave the construction site. The wages are meagre, working hours long (50-60hours a week) in scorching sun, accommodation is in barracks; home journey is allowed once every 2-5 years. Krishna refers in particular to the fact that 1.2 immigrants labour in Qatar and how many and in what conditions they would be involved in constructing stadiums and other facilities for the forthcoming World Cup soccer to be held in Doha in 2022. He draws striking similarities between the Kafala and indenture systems in his words “From the sugarcane fields to the skyscrapers, the life of a coolie has not changed in history. The Kafala coolies labour in the desert sun knowing that they will never be able to set foot in the glittering malls, airports, and stadiums that they are to build. Something must be done about this”

Krishna lays out in stark detail the desperate conditions in India after a long period of British rule that led to indenture and the hardships endured by the indentured labourers from the time they embarked in ships in Madras or Calcutta until the end of their period of indenture. About one third of indentured labourers returned to India as was the case of Viriah, Krishna great grandfather. It remains an enduring question in the minds of South Africa’s Indian community of whether its ancestors should have all returned to India. In the addendum, insightful chapters on Gandhi in India, a brief history of South Africa and the history of sugar cane add to the richness of the book. Viriah by Krishna Gubili makes a significant contribution to the history of Indenture particularly to that of the then province of Natal, South Africa.

Reviewed by Jairam Reddy. Durban, Berea

The book – Viriah by Krishna Gubili; Notion Press, 2018. The book is available on Amazon.com

Very educative column lm a history student lm very much interested in such columns keep it up

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was glued to the “page” and will definitely buy the book. My forefathers came to South Africa from Mauritius in the mid to late 1880s. I have searched for information about this group of immigrants. Could you please assist me? Perhaps give me directions as to where to find the information. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very informative and made interesting reading.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Truly amazing but sad ..

LikeLike

I think we writing about indentured Indians, I was raised on a sugar plantation…. an important aspects is to interview those lived in the plantation in the south coast, the barracks, rations, etc. People living at Sezela, Esperanza, Kelso etc are key to understanding the next of the suffering. Fortunately I studied, went to college. Qualified as a teacher, now a ward councilor and in business in Newcastle

LikeLike

A very interesting read , informative and to the point.

China Gangan

Grandson of Gangan Padavatan

LikeLike

This is an amazing story.

Would love to read the whole book.

LikeLike

While reading this,I could picture my father and maternal grand dad and how they would have suffered slaving under in humane conditions.For a long time,I held strong negative feelings against the races and people’s who inflicted such sufferings and torture on the indentured labourers.I am glad to say that I am healed from those deep seated ill feelings,after having realised that practising forgiveness and love towards them,was the path to follow,as taught by Jesus.

I can’t wait to obtain a copy of this book.

LikeLike